Attending to It

- Logan Garner

- Sep 11, 2025

- 7 min read

The full moon has rolled west and out of view, illumination reduced to a trickle through the black frame of my window, and has hidden itself behind the marine layer, that bank of low-altitude stratus clouds which visits nightly this West Coast. A woman sleeps beside me. An ancient dog snores at the foot of the bed. In the absence of the moonlight, a tiny orange diode glows, suddenly prominent, indicating the low setting of a heating pad, atop which is curled a final slumbering form—a buff tabby, sole occupant of the valley between human-shaped mountains of the comforter. As I sit, observing them, a phrase floats to my mind: Pick something small and attend to it.

These are the words that Dr. Robert Michael Pyle, bearded and longish-haired, used to deliver to me his ethos for writing about nature while we chatted over beers. Part social visit, part interview, the man sat in layers of flannel, half buttoned, and tilted his glass toward me as if to say 'pay attention to this bit.' It was the lesson—and the image—that visits me now.

At the time of this writing I am reading essays, replaying this recent and years-old conversations, contemplating the many writings of Dr. Pyle. Renowned lepidopterist, conservationist, naturalist, activist, poet, and novelist, the man is a giant in many spheres. And I have been tasked with composing an article on him for a regional periodical, with special attention to his most recent book.

This gentleman, consummate master of nature writing, known to me alternately as “Bob” or “Dr. Bob,” is and has been a teacher, mentor, and friend. That I can with both honesty and confidence write such a declaration stirs in me a tremendous sense of gratitude. And yet, I am meant to write objectively about him: without necessarily affiliating him with this genre of "nature writing," into which he so easily fits, but whose label he is not a fan of (he has said as much in workshops, in essays, and in person). All writing, he attests, is nature writing, since 'the human and the more-than-human run together.' A long-time credo of his: we and all that we do or have is of the physical, "natural” world. As I compose this, a band of coyotes lilt and wail from the distant dark outside my open window. I can’t help but hear a question in their voices. 'You-you-you! Hoooow...?' How will you write it? What will you say? And they are right. What can I say to celebrate a man who has so often, so consistently, and reverently held up our place in the natural world for joyful or wary consideration? Which examples or insights shall I call forth from a body of work spanning decades across the spheres of academia, activism, policy, fiction, narrative nonfiction, and (my favourite) poetry? How might Pyle begin this task? The only advice I can follow is the doctor’s own: Pick something small and attend to it. Then look up, look around, report back.

Indeed, Pyle excels in bringing us back to the natural world (of which we are ever a part, despite humanity’s collective insistence on the contrary) through the minute. Consider the examples from his writings: a hike’s pause to rest on a bed of moss. A dipper’s disappearance beneath the river’s surface. The scrabble of a beetle over a scree slope. Each of these moments demonstrates that the “small” is relative. We may more accurately understand the concept of “the small” when we think of what biographer Brian Boyd called Nabokov’s “individuating detail” of a single butterfly, or it may be the whole of a place, like Hendrickson Canyon in the Willapa hills of southwest Washington (itself a diminutive nook in the Pacific Northwest). Regardless of the literal scope, Pyle’s hand lens deftly homes in on this “smallness,” the immediate, before pulling back in favor of some wider view. And so I will attempt to do something of the same.

Let us consider one of his shorter works, then. In 1970, before “Dr.” was affixed to his name, Robert Michael Pyle composed a short essay about the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, now a 70,000+ acre preserve in southwest Washington. While already a veteran essayist for the Sierra Club and the University of Washington’s Northwest Conifer, it was still early in his career. This was to be his first piece in a magazine with the history, reach, and stature of the nationally-distributed Audubon.

With the efficiency of a journalist and the tender care of a lovestruck naturalist, Pyle opens his essay, Willapa Bay, by outlining the breadth, texture, and contours of the wild, picturesque bottom-left corner of Washington. Fluid as the tide, he shifts to its diverse wildlife. The short essay is an estuary of messaging (to exhaust the metaphor), by which I mean that it is incredibly rich in its catalog of awes, and both gradual and sure in its transition to portents: the bay, the refuge and its delicate matrix of biotic systems face a staggering set of threats, not the least of which include dredging and draining of adjacent wetlands and an impending proximity to a new nuclear power plant. It’s a little corner of the world, this Willapa refuge—distant to all but a few in the big scheme of things—and yet Pyle brought it to so many minds, mailboxes, dinner tables, allies...pick something small and attend to it. Then look up, look around, report back.

Though Pyle has written mountainous volumes since then, this early essay sticks with me. Perhaps it is because the bay is so close to his long-time home in Gray’s River, conveying a sense of ownership. Perhaps it is that it’s so close to mine, and so instills my own stake-hold. Whatever the reason, there it is. Pieces like this one explained my first notions of Pyle, a name I knew as an entomologist, conservationist, and activist. His aforementioned advice to me, which came years after our first meeting, was equally about poetry and observations of nature. Indeed, it is consistent with his approach to that early essay fifty-five years preceding this moment.

Pyle’s latest book—his 28th in a career spanning six decades, with at least two more on the way—is a collection of poems eighty-two strong. The Last Man in Willapa, published and released by Texas Tech University Press on April 15, 2024, neatly fits his modus operandi. Each poem grasps an encounter or detail, spends time with it, and turns toward the reader to reveal some value, lesson, or amusement drawn from its present. The collection is divided into five narrow parts: from elegiac odes to a stint in Cuba, to the dusk-playtimes of childhood and singular characters of the lower Columbia, and finally, to songs of rite, ritual, and memory. Each is focused on a particular aspect or section of his life and career.

And inertia they have; they flow beautifully through the collection and move the reader along currents old and new of Pyle’s life. For a man who has shared so much of himself through the decades, this latest book is as fitting a portrait as any. That it is poetry makes it all the more intimate and personal a view, and one that necessitates the inclusion of flora, fauna, and a sense of place, for they are as much a part of him and his work as anything. One poem in particular, The Bats of Havana, demonstrates the close connection between Pyle and place, and comes from his writing expedition to the eponymous city. A whirlwind trip by his own say-so, it is perhaps a fitting window for the reader:

The Bats of Havana

whisk past my shoulder

leaving echoes

of ink and gauze

One of the shortest poems in the book, The Bats of Havana also happens to be one of the author’s favorites. As fleeting as its subject, the piece reminds the reader that even the barest rendezvous can reinforce our inclusion in this connected, complicated, beautiful whole. Even a poem as short at this is not just about one thing.

So it's one more lesson from Robert Michael Pyle: that there is richness in realization of the moment, in acknowledgement of even the smallest creatures, of tiny, wild nooks and crannies. It is the example of being here, now, that Pyle offers in his writing, especially in poetry. It is an example I will strive to follow.

The coyotes are at it again, joined now by chirruping Pacific tree frogs. Their voices, all softened by distance, don’t seem so plaintive now. These are soothing sounds, floodplain lullabies for the sleeping creatures in this little cottage. I look again at each predawn silhouette—the dog curled into a comma, the crescent-shaped cat, the wimpled, blanketed form of the dreaming woman. They are all close, immediate. I listen to the yips and hollers out there, the tumbling rounds of amphibious song, and now the bugling of a Roosevelt elk a good mile off, its call widening the scope of the moment. Here is a distinctly Pyleian opportunity, if I can manufacture the term. Pick something small and attend to it. Then look up, look around, report back.

Logan Garner is a poet from Oregon's north coast. Winner of the Neahkahnie Mountain Poetry Prize and one of Tupelo Press's 30/30 poets for 2024, his work has been featured in Orca Literary Journal, The Elevation Review, The Salal Review, Flying Island and others. He is the author of collections "Here, in the Floodplain" (Plan B Press, 2023) and "The Sin of Feeding Wild Birds" (Broken Tribe Press, 2025).

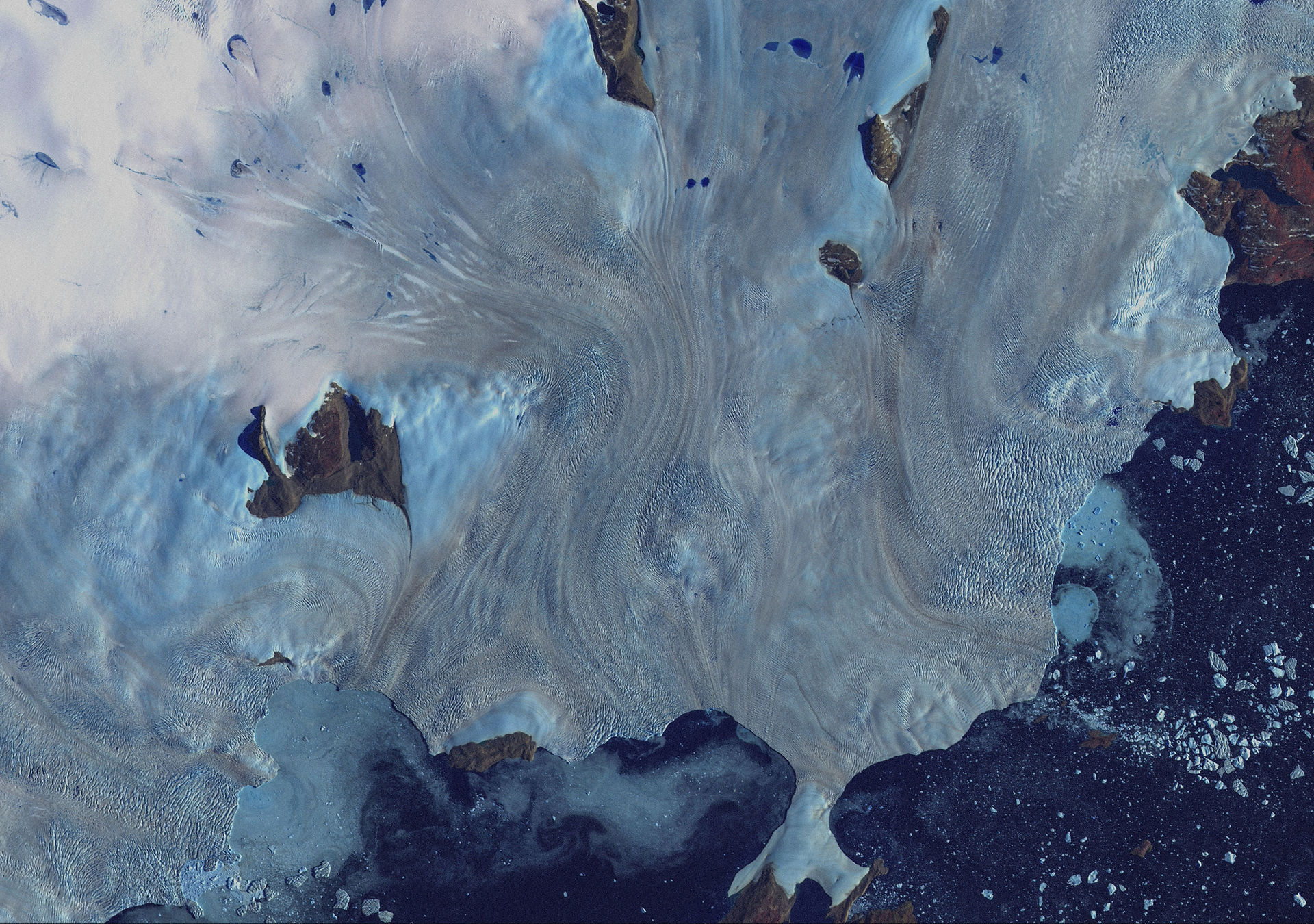

Artwork by Karolina Uskakovych— a designer, artist, and filmmaker from Kyiv, Ukraine. Karolina is a co-founder of the Uzvar_Collective and Art Director for the magazine Anthroposphere: The Oxford Climate Review. She is also artist-in-residence at Re(Grounding) programme as well as the Digital Ecologies research group. Her current research explores traditional ecological knowledge in relation to gardening in Ukraine.

After reading the article on Enclomiphene, I came away with a much clearer understanding of how this compound works differently from traditional hormone therapies. The piece explains that because Enclomiphene stimulates the body’s own production of LH and FSH, it can help support natural testosterone levels without the shrinkage that sometimes comes with external testosterone injections. It was reassuring to see that the research suggests this internal stimulation may preserve or even improve testicular function compared to other approaches. For anyone exploring options to maintain hormonal balance with fewer trade-offs, this article was a great overview.

https://valhallavitality.com/blog/examining-enclomiphenes-impact-on-testicle-size-a-comprehensive-overview